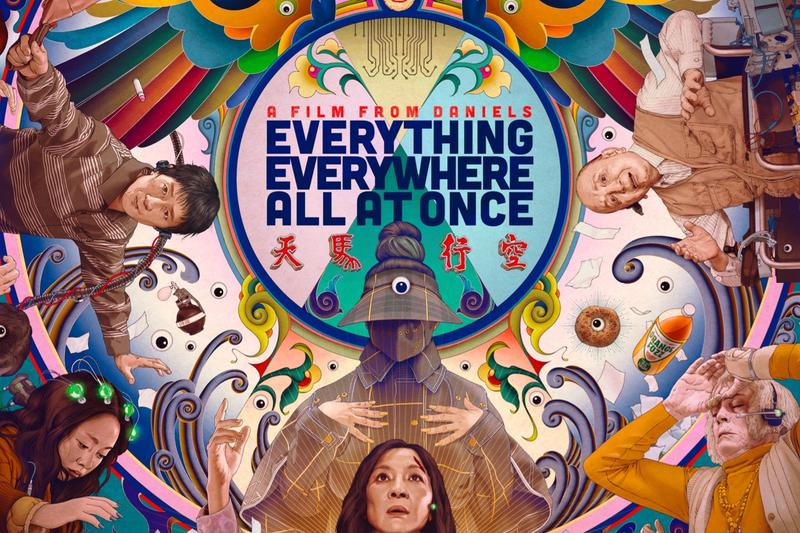

At some point during the end of the third act of directing duo Daniel Scheinert and Dan Kwan (known collectively simply as Daniels) sophomore film, Everything Everywhere All At Once, there is a short sequence of two rocks — one of which is wearing googly eyes — as one tumbles over the edge of a cliff, and, after a few moments of trying, the googly-eyed one tumbles over the edge as well. Watching them tumble, one and then the other, brought me damn near to tears. Along the epi (proper epic), sprawling, imaginative, effervescent, hilarious, touching two-plus-hours runtime, the Daniels had wrung damn near every possible emotion from their audience, and we are much better for it.

The legendary Michelle Yeoh plays slightly against type here as Evelyn Wang, a mother and wife who has long since abandoned her dreams and ambitions for the simpler life of owning a laundromat and taking care of her father (the equally-legendary James Hong). She resides in a settled, unsurprising marriage to Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), a simple and seemingly-silly man who wants nothing more than a comfortable life with his wife, who has come to view her husband as yet another responsibility to watch over. In addition to the lack of excitement and imagination in her marriage, she also suffers from the estrangement that comes with having a daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), who is growing increasingly distant from her parents and, like her mother, sturggles to live up to family traditions and values while breaking off to live her own life on her own terms. On top of all this familial drama, the Wangs are also being audited by a humorless tax assessor (a near unrecognizable Jamie Lee Curtis), and in danger of having their small business repossessed.

Sitting at an audit, Evelyn is suddenly confronted by her husband in an elevator, who tells her that he is not really her husband, but a version of Waymond who can traverse the multiverse, and enlists her help to try to stop an all-powerful villain from destroying all reality, one universe at a time, in an attempt to prove that existence of infinite possibilities nullifies any one personal choice: nihilism as personified by a black hole shaped to look like a massive everything bagel.

The playful aspect of the direction aside (this is a film that starts simply as the story of a mundane tax day before quickly morphing into something so much more expansive), the Daniels exhibit such a playful energy and effervescence that is refreshing. In the Q&A presented after the film premiered at Brooklyn’s Alamo Drafthouse (where the audience — which included some of the cast and crew — was told they were the first to ever buy tickets for the film), Dan Kwan revealed that Michelle Yeoh was always in mind to be cast (although her character was initially to be more in line with Waymond’s).

The film was years in the making, during which time the idea of a multiverse — a universe of reality for each possible choice a character could have made throughout their lives — gained mainstream acceptance and understanding. The idea of a multiverse was no longer a far-fetch idea that would require endless exposition so audiences would not be lost, but was instead already in the zeitgeist, thanks to the films of the DC and Marvel comics universes.

This sophomore effort is also much more focused than their premiere film, Swiss Army Man. Whereas that film played with surreality and dadaism to explore the stages and symptoms of depression, it sometimes meandered and got lost in its own fantasy. While it was certainly fun to watch Daniel Radcliffe as a farting, talking corpse, the former film often got lost in its cleverness.

This sophomore effort keeps itself focused on Evelyn, using the exploration of multiverses to delve into her psyche, her passed opportunities and lost dreams. Evelyn has the ability to tap into the versions of herself from different realities, at once attaining their abilities (singing, gymnastics, twirling, extreme dexterity of her toes due to living in a world were humans evolved to have hot dogs for fingers), as well as their memories. By tapping in, she is able to glimpse the lives she’s never lived, the choices she’d passed up; in one of the more heartbreaking realities (framed and shot as a pastiche of In The Mood For Love), Evelyn lives a reality in which both she and Waymond are both classy successes…simply due to her turning down his proposal of marriage.

The plot is wild, and I won’t spoil it for you, dear reader (although it is not as “out there” as perhaps everyone made it out to be), but it remains heartfelt and earnest due to its laser focus on Evelyn and her relationship to her husband, and her daughter. Ke Huy Kwan is perfectly cast as her seemingly naïve husband, and he uses his past persona as a child star to good effect here: he is almost exactly as I’d remembered him from The Goonies or Temple Of Doom; he can play silly and playful, but there are moments of deep maturity in him as well that make Waymond a stronger, smarter character than the audience was led to believe.

The less mentioned about Stephanie Hsu’s wide-ranging performance as daughter Joy, the better: of every member of the cast, she was the most surprising in her range (and her insane costumes!)

A trend towards overexplaining the mechanics of the multiverse seems to be the major flaw with this film, which otherwise moves at a brisk pace and straddles the line between nihilism and the Buddhist concept of Śūnyatā that it was an almost overwhelming experience. There are wildly inventive (and hilarious) fights scenes, comedic slapstick, and an insanely impressive amount of imagination that actually work to buoy real emotion, the type of which nearly led me to weep in amongst my fellow filmgoers.

Larkin Seiple‘s gorgeous cinematography plays with genre and style so adeptly it is almost intrinsic, and Son Lux‘s evocative score is as beautiful as it is danceable.

As the Q&A afterwards detailed, Dan Kwan used his sophomore film to write what amounts to Millenial experience; being amongst the first generation to grow up on the internet, which inadvertently created an insurmountable chasm between parents and their children: “I am both the child and parent in the relationship now, which is very weird. The relationship [between Evelyn and Joy] had to be so nuanced and specific so it wouldn’t get washed out by the larger story.”

In regards to the casting, Michelle Yeoh had stated that the Daniels had asked her to do things for the film that no director had ever asked her to do (probably the dildo fight…), and at one point she became introspective, remarking, “I can’t help but think what my life would be like if I had made a movie like this earlier in my career.”

The ability to make a film turning negative nihilism into what the Daniels describe as “positive nihilism” took a lot of work, over six years of tweaking and editing and reconsidering what it means to confront lost dreams and passions, and whether those choices are even worth losing the reality of The Now.

The multiverse is an infinite look at infinite possibilities. This film is worth that journey. I cannot possibly recommend this movie enough. 4.5/5 Everything Bagels.

Everything Everywhere All At Once is playing in select theaters, and opens wide on March 31st at theaters.