In a summer full of Ultrons, Terminators, Ant-Men, Jurassic Worlds and whatever-the-hell is going on in Tomorrowland – theater goers are going to be inundated by parables of science gone wrong. For that reason, Alex Garland’s directorial debut, Ex Machina, couldn’t have come at a better time. Evil robots have always been a mainstay of the sci-fi genre, but in an age where we’re closer than ever before to true artificial intelligence– it’s surprising that there are very few films that really ask any meaningful questions about consciousness…

There was 2001, Blade Runner, more recently Her, and now we can add Ex Machina to the mix. While Garland’s film is really an isolated thriller at its core, it still succeeds at finding interesting ways to add to the ongoing conversation in the science community about the validity of the Turing Test, the ethics of the process of creating sentient beings, and the role of emotional intelligence in AI.

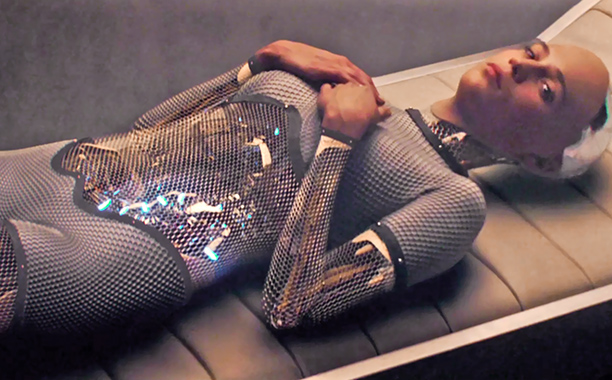

In Ex Machina, Domhnall Gleeson (About Time, Black Mirror) plays Caleb, a programmer at a Google-esque web company called Bluebook. Caleb is randomly selected by Nathan, Bluebook’s mysterious CEO (played by Gleeson’s Star Wars: Episode VII co-star Oscar Isaac, of Inside Llewyn Davis fame) to join him for a one week stay at his massive, secluded estate. Caleb comes to find out that Nathan’s home also comes with an extremely technologically advanced subterranean bunker where Nathan has been working on developing true artificial intelligence for the better part of a couple years. It is there, Caleb finds out that he’s going to be the human component in administering the Turing Test to Nathan’s sentient robot, Ava (Alicia Vikander – Seventh Son, 2015’s The Man From U.N.C.L.E).

For the uninitiated, Alan Turing (you know, the guy that Cumberbatch played in The Imitation Game) developed a test to determine whether a machine had the ability to exhibit an intelligence that was equal to that of a person. Simply put, if someone could not tell if a machine was really a machine, then Turing believed it to have true artificial intelligence. It’s important to note what the Turing Test is because the majority of Ex Machina both questions the validity of the well-renowned test, while using the idea of a proper test of AI as the backbone for the suspense in the plot.

Ex Machina‘s story structure feels very familiar to a lot of Garland’s other previous works. Like Dredd, all the action takes place in one singular location. The conflict ramps up in the third act, stemming from character motivations that comment on the psychology of mankind in outstanding circumstances, as it does in 28 Days Later and Sunshine with the third act paying off more like 28 Days Later and not so tonally jarring as it was in Sunshine. Yet, in every other aspect, Ex Machina feels very completely different from anything else he’s ever done. Now that he’s also in control of how his script is being directed, everything has much more of a sense of purpose than it ever had before. The tone is cohesive, even as it makes the signature Garland turn from wondrous to dreadfully tense. It’s only helped by the steady, methodical pacing that gives as equal weight to the plot developments as it does to the philosophical inquiries, of which there are many.

As the story unfolds, Caleb is constantly pushing to modify the Turing Test with intellectual solutions while Nathan tries to get Caleb to react more emotionally. Nathan even tries to get Caleb to think about how he feels about Ava, and “more importantly. How does she feel about you?” That question that Nathan poses to Caleb is the crux of what makes this film stand out from everything else in its genre.

The character of Ava is not a McGuffin, she’s a fully fleshed out character with her own secrets and motivations. Her point of view is just as integral to the story as Caleb’s and her existence draws out the more thoughtful questions that Ex Machina has to ask. How do we define consciousness? How do we synthesize it? How would we test that in a machine? How would we know that the test is completely valid? When does that consciousness indicate that there is actual life? What does that make the person who created it? Then there’s the question that Ava asks Nathan, which is kind of a spoiler, “Isn’t it strange, to create something that hates you?”

Thanks to Garland’s dialogue and the performances of the three main leads, the characters aren’t merely voice boxes for opposing views on artificial intelligence. Every question asked reveals something about the character that asked it, and every answer given raises the tension even higher. Gleeson does a fine job at turning an agreeable audience surrogate into a fully fleshed out character that influences the plot, and the more I found out more about Nathan, the more I was impressed with Isaac’s performance. On the surface, Isaac is channeling a ‘bro’ version Justin Timberlake’s Sean Parker; but what he’s really doing is his own little balancing act that makes sure the revelations — that are made about his character by the midpoint of the movie — don’t betray how he played him up until then.

Then there’s Ava. The VFX team beautifully mixed CGI with practical effects for her look, but it would have been all for nothing if she wasn’t brought to life by Vikander. Because of her character’s synthetic form, Vikander had to couple non-human motion with human emotion. She didn’t go the route that most actors do when they play robots; instead of cold, she went inquisitive. Everything was wondrous to her, like they would be to any life form that was just recently created. Couple that with the fact that her inhuman movements weren’t stilted (like the “do the robot” dance), but more precise and determined, which matched perfectly with the tone of the film itself.

Sadly, Ava will soon be overshadowed by her louder, more evil, robot cousins later on in the summer season, but she’s sure to stand out as the most unique, nuanced movie bot by the time the year is over.