It’s hard to argue the fact that when it comes to science fiction and horror, women tend to get short-changed. They’re the ones to run around in the dark, groping for some sort of protection against a raving psychotic murderer, at once both the victim and hero (Scream effectively played with this stereotype, before ultimately succumbing to it in later sequels). Either that, or they’re in peripheral to the male characters in a sci-fi action film: sidekicks or love interests, but somehow otherwise attached to the more masculine, interesting, developed male counterparts.

Now, of course, there are exceptions. But, let’s look at the geekiest, long-lasting genres, the ones that see the most releases per year (prior to the onslaught of comic book properties, of course). We’ve got science-fiction and horror films. And rarely do these films focus on, and delve into, the female psyche and perspective in a profound way.

Now, that being said, let’s talk about two of the best films from 2014: Under The Skin and The Babadook, and how they turn that sentiment around.

The Babadook is a small film directed by first-time Australian Jennifer Kent that says more about being a single parent — specifically, and importantly, a single mother — than it does being a straight-up horror film.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szaLnKNWC-U

The film stars Essie Davis as Amelia, a depressed single mother living in a lifeless, oppressively dour home with her young son Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Her son is ravaged by nightmares, hyperactivity, and, as such, has not adjusted well to being with other kids. He devises makeshift booby traps for imaginary monsters, and is needy and yearns for attention and validation from his mother.

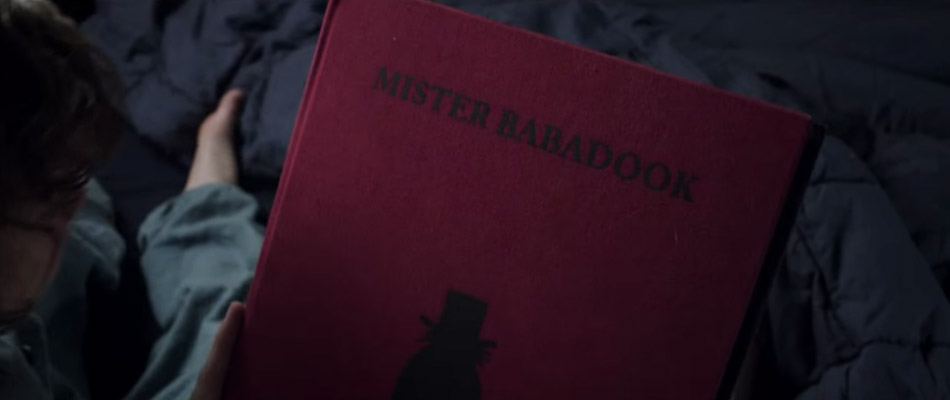

Physically, she is a wreck. Her hair haggard, with eyes bulging from within deep bags, Amelia cannot escape the overwhelming needs of her son, not even for a few minutes at night to use her vibrator (the scene produced a few giggles, but had the intended effect: woman just can NOT get a minute to herself!) She reads to him every night before he goes to bed, so when they both happen across a red-lined book called Mister Babadook — a book they’d never seen before — they take a read.

Soon, mysterious (and dangerous) happenings occur in the household, threatening not only the sanity of Amelia, but also her and Samuel’s lives.

The horrid actions the Babadook inflicts on the family is not even done by his own hand, but through the hand of Amelia. And it is here that the film takes a deeper look at this family dynamic. Throughout the film, Samuel had imagined make-believe monsters throughout his life, so what would make the Babadook any different? And theirs is not at all a happy home: At an awkward birthday party, Samuel off-handedly tells an adult that she resents him. His father had been killed in a car crash taking Amelia to the hospital to deliver Samuel; if he’d never been born, he says, then daddy would still be alive.

The weight of that guilt, and the resentment his mother must have felt (and she must have felt, and probably articulated, it at some point—a kid that young doesn’t say something like that without hearing it from somewhere first) does a number on anyone, let alone a kid.

But, much like the thematically similar The Shining, The Babadook is about parents relinquishing the responsibility of being a parent, and about children being threatened by the very people they should always be able to trust. Whereas The Shining ends with Danny retreating to his mother’s embrace, and she summarily leads them both to safety, The Babadook shows Samuel being the one to take control. He restrains his mother and talks her down, and he’s the one to eventually save her.

Here, it is the child that assumes the protector/savior role, being either more mature (or, perhaps, allowing his ripened imagination to see the Babadook for what it really is), while his mother succumbs to her basest fears.

Here, the deeper message of motherly disdain and resentment comes to the forefront. Amelia, her resentment at full, and (whether due to the reality of the Babadook, or merely the illusion of it), at several points lashes out at her son; first, through his imagined fears, then through their pet, and finally directly at him physically.

Here, she blames him for her failures and unhappiness, for the loss of her husband and social life. In these moments, The Babadook‘s presents the scariest reality for a parent: that they may bring harm — deliberate or otherwise — to their child (and for a mother to face that reality must be doubly grim to bear).

The film is psychologically terrifying, in its allowance of these taboo thoughts of blame, resentment, neglect, sexual frustration, and even infanticide to be thrown so starkly and nakedly at the audience. It is no surprise that these distinctly maternal instincts are so blatantly explored and disbanded in a film directed by an accomplished woman, in a genre dominated mainly by men. These are taboo thoughts that, at one point or another parents (or, in this specific case, mothers) never want to acknowledge, the film seems to say.

By the end of the film, Amelia has at least made peace with the Babadook (whether it be real, or otherwise) and acknowledges its presence, even keeping trapped in the deepest, darkest corners of her home. It’s there, she knows it’s there, but she’ll never let it out again. And in this way, she and her son can be free and happy.

Under The Skin opts not to be a straight adaptation of the source novel by Michael Faber, instead director Jonathan Glazer keeps the story purposefully ambiguous, using Scarlett Johansson‘s nameless alien character as a cypher to explore modern female gender roles in a society gone strange.

The plot, in a nutshell, involves Johansson’s alien, human-disguised character skulking the Scottish moors and highlands and seducing young, mainly boorish men and luring them back to her lair, where a viscous black liquid slowly liquefies them for…some reason. Her character is purposefully nameless, distant, and — not just for the star power — deliberately ridiculously attractive.

She is nothing but a pretty face; what’s her name?

Who cares.

Why does she want these men?

Who cares.

How does she live, eat, sleep, learn English, know how to drive a car?

Who cares.

Where is she really from?

Duh.

These questions don’t matter to the story, because they wouldn’t inherently matter to her victims. To them, she’s nothing more than another lay, another conquest and pretty face. She understands the easiest way to get a man to do what she wants is to promise them sex, but she has no understanding of what sex even is.

It can be argued that her character doesn’t even understand what being attractive is: in a scene where she picks up a severely disfigured man, he treats her kindly and equally, not with the boorish lust of her previous victims. It is only when she touches his hand that he agrees to follow her home. His reaction is the one that disorients her understanding of humans: she ultimately lets him go and tries to move away from her mission.

At times, Under The Skin felt like a companion piece to Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth. In addition to its meandering plot and similar alien designs, both films explore gender roles from the perspective of a character who has no understanding of how gender roles are even supposed to work– or even why. Whereas Man… explored an androgynous alien (played by David Bowie) getting caught up and obsessed with traditionally “male” goals such as wealth, technology, alcohol, drugs, power, status, and — by far, and above everything else — sex in all of its myriad forms, Under The Skin shows the opposite side of the same coin. By making the alien female, the film shows how strange and almost arbitrary modern gender relations (and typical gender roles) tend to be, as she would have no concept of gender differences.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NoSWbyvdhHw

To an audience cued into these roles, the film is jarring: she does not understand there is a maternal instinct to respond (or at least acknowledge) a crying baby; she does not understand the significance of a man giving her a rose; nor does she anticipate any danger for a well-dressed, attractive woman like herself to be sitting, alone, in a van at an empty parking lot, surrounded by teen-aged boys.

The two most compelling scenes occur near the end of the film. In a scene where Scarlett’s character is attacked and assaulted by a park ranger, she makes no attempt to call for help, nor does she seem to anticipate what will presumably happen to her. She has no reason, being on her own out in the woods, to fear anybody, especially a man; nor does she have any reason to believe that she is not at least physically his equal (especially since she so easily dispatched scores of men throughout the film); nor does she have any reason to think of calling for help. This is not at all to call her character naïve or stupid (far from it), merely to illustrate one of the recurring motifs of the film: she does not understand the danger of being a woman today, and that misunderstanding brings out the basest nature in others (or, from this film’s perspective, brings out a purely masculine nature).

Yet, on the other hand, a separate exploration of human nature (at once both base and altruistic) immediately precedes this scene.

When her character decides to explore the country on her own, a good Samaritan picks her up, cleans her up, offers her food and a room, and buys her goods that she needs. After a time, she grows comfortable enough to explore sites with him. After a time together, he attempts to be romantic with her, and they undress. As he begins to enter her, she bolts up, startled, grabs a light, and examines herself. The act of penetration itself is so foreign — so utterly alien and confusing — that she retreats completely, abandoning these creatures with whom she’d surrounded herself and hiding out in the woods.

As a human female, nothing in the world makes sense to her and she is forced out on her own (to a devastating end).

Both of theses films feature strong female characters, each of whom fluctuate between falling into stereotypical tropes, and overcoming them in surprising ways. The Babadook starts with a weak woman confronting her worst instincts and unspeakable doubts and becoming stronger for it. Under The Skin starts off featuring a strong, cold, calculating dangerous woman who eventually suffers for exploring her own humanity and femininity. Two sides of the same coin, told in unique ways.

Both The Babadook and Under The Skin are worth seeking out and supporting. Both films explore tropes while still leaving so much thematic material to mine and discuss. The female perspective in genre films has brought about some of the classics that we geeks love (Alien, Halloween, the aforementioned Scream, Wonder Woman, the Modesty Blaise series, and The Descent immediately come to mind), and it is refreshing to see two new unique views added.

Not to mention they’re both damned fine films to boot.