This past weekend, yours truly and Lisa Wu attended the Big Apple Comic Con, one of the older comic and geek conventions in the New York City area. Spanng the main convention space of the Pennsylvania Hotel, directly across from Madison Square Garden and Penn Station, it was a full, geeky affair with more than one surprises– and plenty of cosplayers.

HIT THE FLOOR

Our first stop was to the autograph area, where we spent a few minutes speaking (off the record) with Data himself, Brent Spiner. Leaning back against a wall, he seemed at home: relaxed, cool, collected, and seemingly in need of authenticity in his interactions. The photos we snapped were off-the-cuff interactions between himself and his fans, who waited eagerly behind us for a chance to shake his hand and take a photo. Across from him sat Mike Colter, Luke Cage himself, who had no shortage of fans, and seemed to enjoy the energy and enthusiasm of those who came to see him. On the table behind Mr. Colter was a long line of fans waiting for William Shatner to arrive; his flight having been delayed, it would be some time before he’d be there.

PHANTOM IN THE TWILIGHT

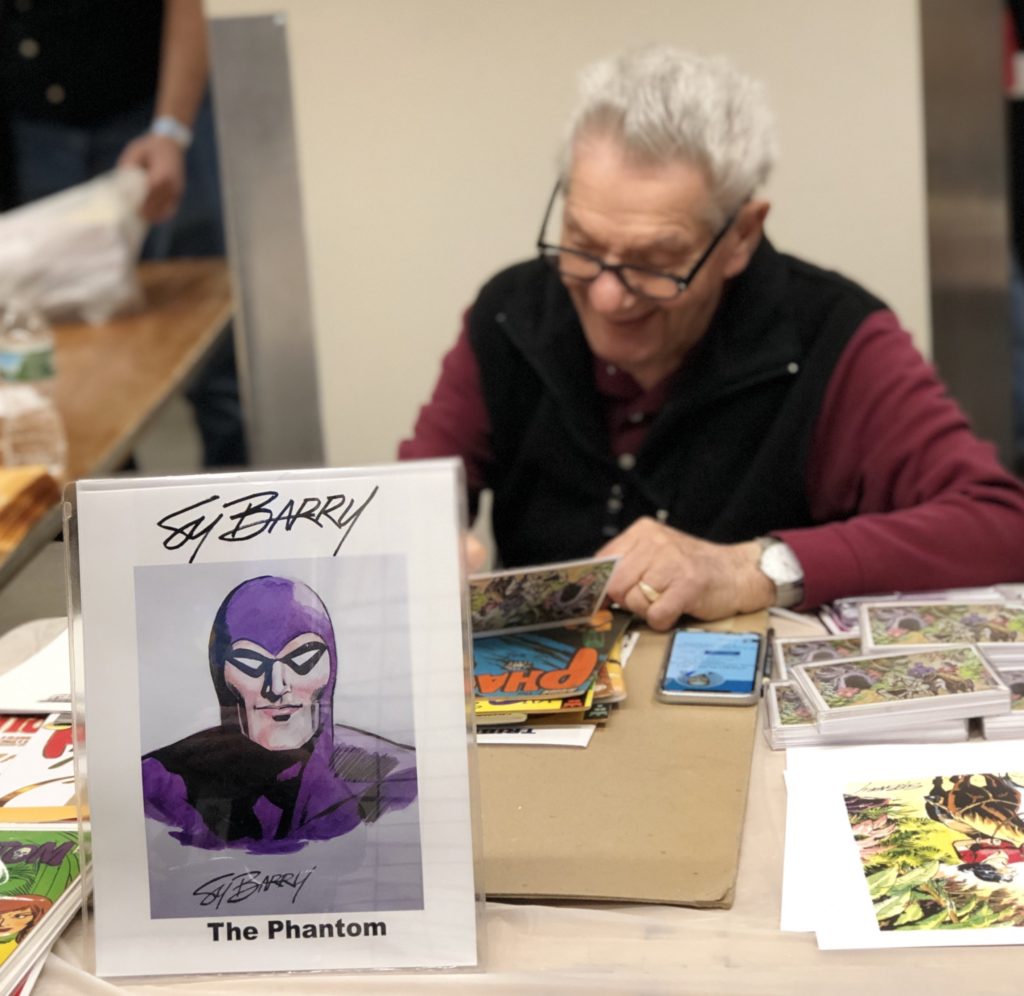

The artist alley, however, was where the action seemed to be for me, as it’s always the place to learn the ins and outs of the industry. Among the artists signing and selling their work was Sy Barry, a veteran of the Silver- and Bronze Ages of comics, who was gracious enough to spend a few minutes humoring my inquisitive self.

Celebrating his 91st birthday this upcoming Tuesday, Mr. Barry took over drawing duties for the Phantom in 1961, working alongside creator Lee Falk, and continuing with the series all the way up until his retirement in 1995. Currently, Mr. Barry enjoys limited speaking engagements, and attending conventions here and there. Of his recent travels, he explained his overwhelmed reaction to first attending the San Diego Comic-Con back a few years ago; the culture having shifted to such enormous proportions to what was normal during his tenure, he compared the works of modern artists to what he witnessed back in the 1960s. “I’m constantly amazed by the creativity, by the use of technology, by what these artists can do now.” he exclaimed, shortly before commenting on the state of modern superheroes.

DOOM PATROL

“Nowadays, heroes are anti-heroes. Back when (I was drawing and working), heroes would come in and save the day. Now, they (sort of) wonder whether they should. Like they almost let things get worse before working to make it better again. It sort of reflects where we are now, not just with stories, and normal people, but politics and everything. Everything is so aggressive.” Does that shift in storytelling benefit the reader, though? “I think it does. It falls in line with reality, which can be ugly and mean sometimes.” To close out our brief interaction, I asked about his view of modern comics, and whether the intermingling of tones and thematic elements are a benefit for readers.

“Oh, I’m not too happy with how stories are told. For kids, it should be a little easier to tell the difference between right and wrong, and good and bad…I marvel at the creativity now…” but it seemed that his skills and stories are part of a bygone era, and perhaps a simpler time of storytelling for comics. During his tenure, Barry and other artists need not worry about how their stories would translate to other mediums, be they television, or movies, or video games. The industry has gotten much larger than what it was, and comics are no longer just a printed world, but a literal universe; stalwarts such as Mr. Barry are a reminder of how far the industry itself has come in just a few short decades.

TOONING AROUND

Wandering around the rest of artist alley, we next met none other than the co-creator of Ren & Stimpy, Bob Camp (who, yes, is as animated and energetic as you might expect). Sitting back behind hand-painted prints from Ren & Stimpy, Mr. Camp — who insisted he’d be called Bob — had no shortage of stories to tell…as well as no limit of disdain for cartoon producers and executives.

“Oh, working on SpongeBob is a lot easier than working on any other show. I come in, do some character designs, and that’s it. They say, ‘Oh, we want Squidward to look tired, or angry or something’. And then I come in, and paint the close up, and that’s that.” On his influences, Mr. Camp immediately named Bob Clampett’s classic Warner Bros. cartoon, “Duck Tracy”, a parody of Dick Tracy, starring Daffy Duck. I immediately recalled the episode; as the narrator introduced parodies of Dick Tracy villains, the characters appear as a painted image on the television frame. These character introductions are the direct influence of the Ren & Stimpy (and SpongeBob) trope where a close-up — usually of a grotesque or otherwise shocking, humorous image — is thrown onscreen for a few seconds.

Not short on anecdotes, I was surprised to learn that Mr. Camp produced the first cartoon to ever be created digitally, the Ren & Stimpy episode “Out West”; prior to this episode, cartoons were commonly hand-painted and hand drawn, render on film, and composited together in editing; Mr. Camp had instead introduced a new work-flow into animation that cut down on the work and time taken to render a cartoon. Wrapping up our brief session, it was clear that the jokes within Ren & Stimpy about producers and cartoon executives seeking attention and praise while doing little actual work to earn it was genuine; he was not a fan of corporate bureaucracy, and even less interested in executive politics as well. Sitting behind his table, showing off his hand painted sketches and renderings of R&S, Mr. Camp spread his arms out, as if to encompass all of his work.

“They won’t let me make any more Ren and Stimpy cartoons,” he said, an effusive smile scrawled on his bearded face, lighting up his bespectacled eyes party hidden by a black fishing hat. “Now I get to make new ones, one picture at a time.”

ONLINE ONLY

A personal friend of Lisa’s current artist Reilly Brown was our next person of interest (having learned that the legendary Jim Steranko was not in attendance). Reilly — an artist who worked on Deadpool, and Cable, for Marvel in the past — was promoting his latest online comic, Outrage. The comic — which is available to download for free via Web Toon — has the selling line of “Who bullies the bullies on the internet?” It features a hero who is able to manifest himself through any online screen to, in a way, troll the trolls.

After founding both Ten Ton Studios in 2004, and Hypothetical Island Studios in 2010, Reilly prefers the online world of webcomics to physical, printed work. “There’s an ability to surprise the reader when you’re online,” he said. “When you’re reading a comic, a magazine, you can still at least see the next page, the next image, if even just from the corner of your eye…we make online images in such a way that we can shock the reader. They don’t know what’s coming.”

Reilly explained how the ability to hold a reader’s attention in a way unavailable to conventional comic readers makes for new, interesting, and exciting ways to tell new stories in new ways. While a lot of the artists present were comfortable (or at least familiar) with working in the printed world, for Reilly Brown and his fellow artists, they were looking to the latest technology to push storytelling and comic art into exciting new places. In this alley of old-school artists was someone pushing the medium to the future.

-J.L. Caraballo, with photography from Lisa Wu