I first encountered the work of Sam Raimi at a church lock-in in 7th Grade. It was October and the chaperone thought it would be cool to rent a couple scary movies. After the more wholesome church-related activities and ritualistic devouring of the pizzas and the sugar, the twelve of us unrolled our sleeping bags to curl up and watch something great. We chose Evil Dead 2 . . .

Within five minutes, this seemed like not only the best decision we could have made under these circumstances but maybe even the best movie experience any of us had had since the throwdown at the Ewok village, those little guys chanting “Yub nub!” at the end of The Saga. It’s challenging to encapsulate how hard Raimi blew open the doors of my brain in such a short time. His insane-velocity tracking shots, the over-the-top mayhem, the splatter-gore past the point of excess, and best of all, the demon-POV shots cribbed from Friday The 13th but lent a new poignancy by their seasick lurching momentum and perpetual snarls, inspiring the sobriquet “Satan on a Moped,” which we all hollered with joy every time it cut to one of those.

The impossible unkillability of Bruce Campbell’s Ash, who we all adored from the first frame. The fact that this was all unfolding on a Friday night in a house of God charged the proceedings with an enhanced aura of transgression. It was a very progressive Episcopal church.

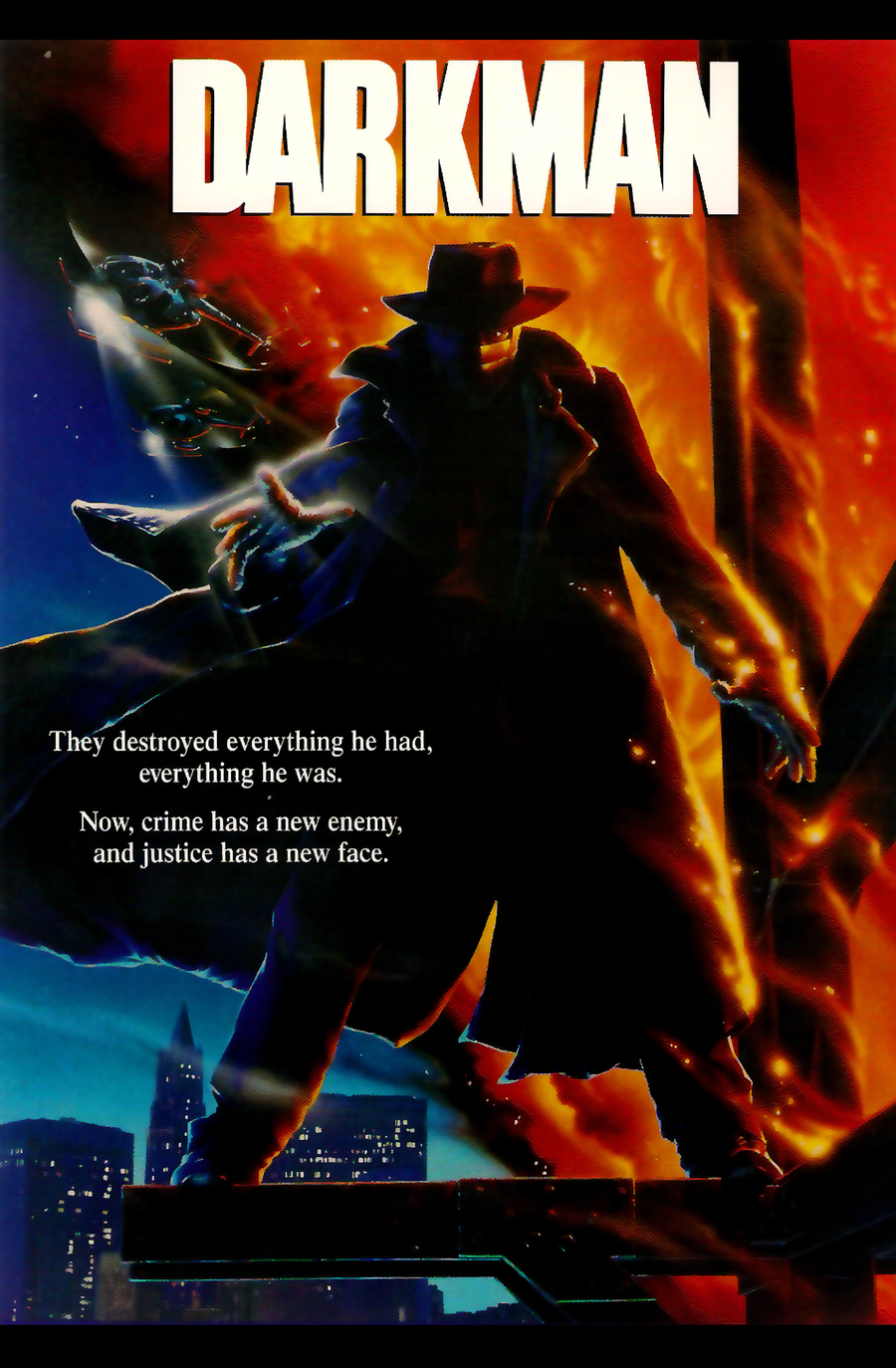

The next time I found Sam Raimi was the following year when he turned out to be the creator and director of Darkman, a new character rooted in The Shadow and Batman who wound up closer to the Phantom of the Opera.

I was thrilled by the WHO IS DARKMAN? ad campaign, clipped an article from the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal to pin up on my wall, and had my mom and little brother there for opening matinee that last Friday of summer before 8th Grade. This was the first time I ever saw Liam Neeson or Frances McDormand, and Danny Elfman’s thunderous score imbues the proceedings with a thematic continuity dialed into Burton/Keaton’s industry-shattering run through Gotham the previous summer.

As the film progresses, Darkman turns out to be muuuuch more psychological horror than pulp superhero adventure with initially sympathetic Peyton Westlake (Neeson) disfigured for his origin story but then driven to commit increasingly horrifying acts of violence in revenge upon those responsible. Raimi repeats this one trick where he zooms into Westlake’s eye to launch another really wild montage of explosions and other disturbing imagery to illustrate the character’s mental collapse.

My favorite one of these happens in the clip below when our hero is trying to win his girl a pink elephant at the carnival, then feels like he’s being treated unfairly. Montage detonates right at 1:32, but the entire two minutes is extremely compelling footage as a time capsule not only of early Neeson/McDormand [37 & 32 years old at the time] but also one of the better superhero movies of the 1990s that did gangbusters box-office ($48.9 million on a $14-million budget) but that has been relegated to deep-cut cult status despite the pedigree. I love the hell out of this movie, but when Raimi & Neeson opted out for the sequels, I did the same. Here’s hoping that they reconvene before it’s too late for Darkman IV: The Return of Westlake or just a proper Darkman II.

Raimi tried on a few different genres in the nineties. He returned to Bruce Campbell and the Evil Dead with the beloved studio 1992 sequel Army of Darkness, tried on the western with The Quick and the Dead (a screaming-insane 1995 cast, if you have not yet had the pleasure), riffed on his friends and students the Coen Brothers’ neo-noir aesthetic with A Simple Plan, pitched one last baseball movie for Kevin Costner in For the Love of the Game, then closed out the decade with a paranormal murder mystery written by Billy Bob Thornton starring psychic Cate Blanchett called The Gift (another appalling cast).

Then, Spider-Man…

We’ve all seen it. Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst and James Franco and Willem Dafoe. The iconic J.K. Simmons roaring with laughter as J. Jonah Jameson. Rosemary Harris, the only actress to ever physically resemble Aunt May of the comics. Elfman back with another bombastic orchestral theme. It still felt like a Raimi movie, sincerity bordering on campiness while never quite over the line.

But the rough edges from the eighties, the indie budget vibe of Evil Dead and even Darkman, that was all shined up. Cutting-edge big-studio CGI let our friendly-neighborhood hero swing through the steel canyons of Manhattan with the greatest of ease while Raimi’s soaring tracking shots presage the motion of a certain Cloak of Levitation through these same avenues twenty years later and in the blink of an eye.

In the six years following Raimi’s last installment of the Maguire franchise, he directed a horror film written by his brother and a Wizard of Oz prequel starring Franco but then nothing for the past decade. Until the Multiverse of Madness.

When Raimi was announced as director of Benedict Cumberbatch’s second turn in the lead role after hovering around quite a lot these past six years impacting other central protagonists’ narrative, I was bummed that Kevin Feige wasn’t bringing him in to revisit Spider-Man for No Way Home. But of course, Jon Watts delivered such strong work with the first two Tom Holland films, it made no sense to change that up, and maybe Raimi could channel some of his early-career energy to guide Stephen Strange away from the baseline MCU quippy superhero-tone and more in the direction of horror.

Reader, even after three decades of knowing (and feeling known by) Sam Raimi, I was not prepared.

In the parking lot Thursday night afterward, I wrote that the film was “aggressively Raimi.” Others have paraphrased the familiar construction “It’s the most Raimi film that ever Raimi’d.” I remain shocked by how his directorial choices here both completely suit and enhance the tone of MCU Movie #28 while simultaneously tapping all the way back to his earliest work.

It’s like Raimi conjured a portal for his 1990 self to pop through to remind himself exactly how he used to do it in the Evil Dead eighties, the things he’d just learned and was about to use for Darkman. All the hallmarks detonating here before us just as fast as they can:

-The long fluid tracking shots

-The lurching antagonist POV

-The completely over-the-top gory madness

-The spastic demons cackling and taunting the hero, lifted verbatim from Army of Darkness

But that zoom into-the-eye montage, the Darkman deal. It happens here. More than once. That annihilated me, immediately portaled right back through the bulging eye to 1990, Neeson losing it on the midway. Then it happens again. And again. Maybe a fourth time. I don’t know. It all started breaking down. I’m unclear how many of my fellow Thursday-night premiere viewers were also long-time Raimi fans, but the accrued progression of all these choices stacked up on them as well.

This escalated the situation into this pretty much demonstrative religious experience the entire back half through, most watchers on this earth pretty much giving up losing their minds, folks started jumping up out of their chairs to then merely stand stock-still aghast, hands over their mouths, or then others just yelling “NOOOOoooo!!” at the screen or then still more stagger sloppy-crying in the aisles when it all really started to go wrong. The last ten minutes, I was really grateful to realize that probably we were all just extras on Page 19 of a Morrison comic cranked out in his 29th year at Marvel. That is how hard it broke down by the end of the 9:20 screening in Theater #13 at the Pflugerville Tinseltown.

Yes, to fully even understand what’s happening with the plot of Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, you need to have a graduate-level understanding of the plot mechanics of at least four other films and one season of heartbreaking television. But the really sublime thing about this movie is that it’s the product of a studio known for sublimating the voice of its directors in favor of a house “Bullpen” style (James Gunn being the real exception here), but then somehow, here we have Feige hiring one of the most versatile and underrated American directors of the modern era and encouraging him to flex his creative vision into a capstone culmination of his entire body of work.

I was powerless not to be portaled right back to my sleeping bag in the church on that unforgiving stiff rec-room carpet when I was 12, high on sugar and friendship and staying up too late and the wild impossibility of all this energy exploding off of the tiny screen at the front of the room, that someone could do this, capture stories the way that I saw them in my head, this kinetic and cackling-mad insane, that movies could go this fast. That they could be this much fun. 4.5/5 “Gimme Some Sugar, Baby!”s.

-Rob Bass